Achieve 60 FPS Mobile Animations with CSS3

This article was originally published on OutSystems. Thank you for supporting the partners who make SitePoint possible.

Animating elements in your mobile application is easy. And animating elements in your mobile applications properly is easy, too… if you follow our tips here.

While everyone uses CSS3 animations in mobile these days, many do so incorrectly. Developers often disregard best practices. This happens because people don’t understand the reasons why those practices exist and why they are so vigorously endorsed.

The spectrum of device specifications is wide. So if you don’t optimize your code, you will deliver a sub-par experience to the highest share.

Remember: some high-end flagship devices push the envelope, but most of the world uses the type of device that, when compared to those spec monsters, looks like an abacus with an LCD screen.

We want to give you a hand in harnessing the power of CSS3 correctly. To do that, we need to understand a few things first.

t

Understand the Timeline

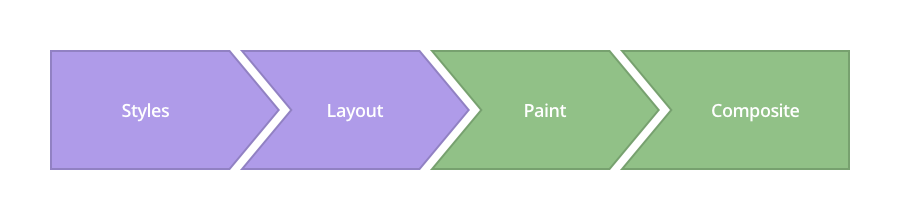

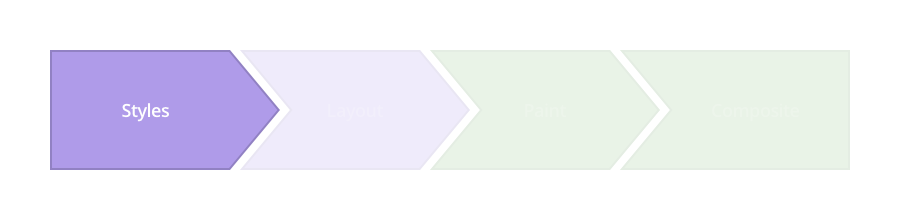

What does the browser do while rendering and playing around with elements? This timeline is called the Critical Rendering Path:

Image Source: www.csstriggers.com

To achieve smooth animations we need to focus on changing properties that affect the Composite step, instead of adding this stress to previous layers.

1. Styles

The browser starts calculating the styles to apply to elements — recalculate Style.

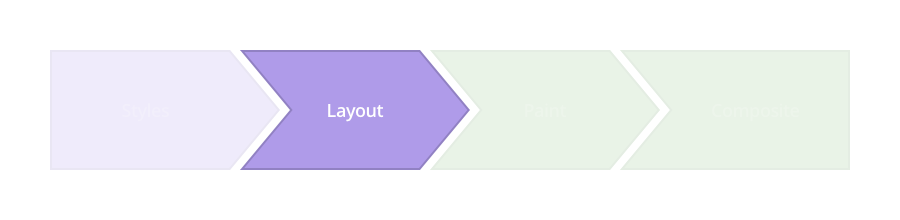

2. Layout

In the following layer, the browser generates the shape and position of each of those elements — Layout. This is where the browser sets the page properties such as width and height , as well as its margin or left/top/right/bottom, for instance.

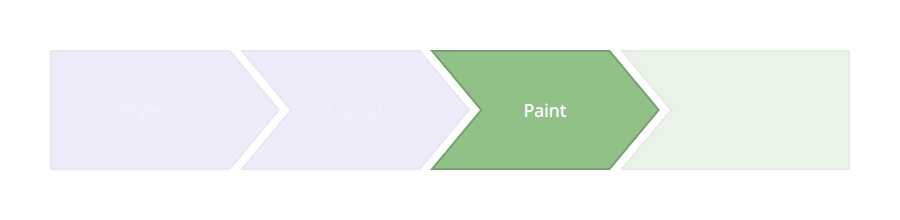

3. Paint

The browser fills in the pixels for each element into layers. It refers to these properties: box-shadow, border-radius, color, background-color, and others.

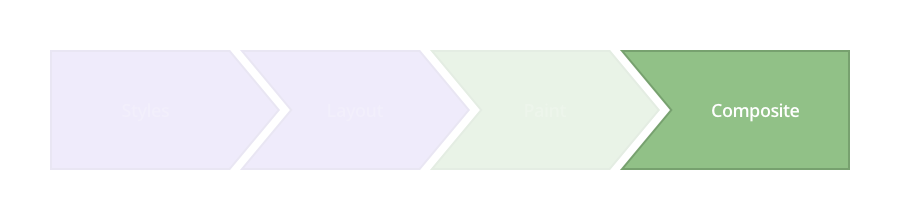

4. Composite

This is where you want to perform your animation, as this is when the browser draws all the layers to the screen.

Modern browsers can animate four style attributes pretty well, making use of the transform and opacity properties.

- Position — transform: translateX(n) translateY(n) translateZ(n);

- Scale — transform: scale(n);

- Rotation — transform: rotate(ndeg);

- Opacity — opacity: n;

How to Achieve 60 Frames Per Second

With this in mind, it’s time to roll up our sleeves and get to work.

Let’s start with the HTML. We’re going to create a very simple structure and put our app-menu inside a layout class.

<div class="layout">

<div class="app-menu"></div>

<div class="header">

<div class="menu-icon"></div>

</div>

</div>

Going About It the Wrong Way

.app-menu {

left: -300px;

transition: left 300ms linear;

}

.app-menu-open .app-menu {

left: 0px;

transition: left 300ms linear;

}

See the properties we changed? You should avoid using transitions with the left/top/right/bottom properties. Those don’t create fluid animations because they force the browser to perform a layout pass each time, which affects all of the element’s children.

The result is something like this:

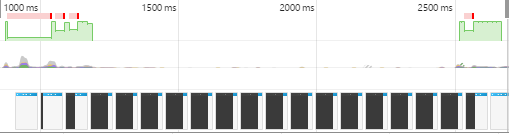

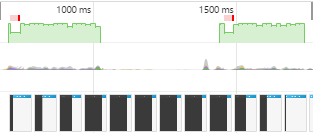

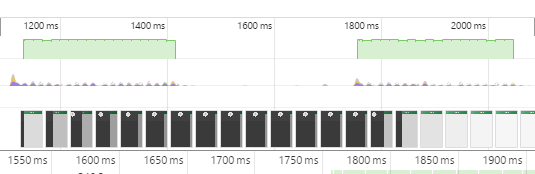

That animation is not too smooth. We checked with the DevTools Timeline to see what was happening under the hood, and this was the result:

Green areas represent the time spent rendering an animation.

This data presents irregular frame-rates and slow performance.

“The green bar indicates FPS. A high bar indicates that the animation is rendering at 60 FPS. A low bar indicates sub-60 FPS. So, ideally, you want the green bar to be consistently high across the Timeline. Those red bars also indicate jank, so, alternatively, another way to gauge your progress is by eliminating those red bars.”

Thank you, Kayce Basques!

Using Transform

.app-menu {

-webkit-transform: translateX(-100%);

transform: translateX(-100%);

transition: transform 300ms linear;

}

.app-menu-open .app-menu {

-webkit-transform: none;

transform: none;

transition: transform 300ms linear;

}

The transform properties affect the Composite step, rather than the Layout. Here, we inform the browser that our layers are stable before the animation begins, so we experience fewer hiccups when rendering the animation.

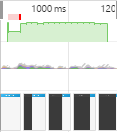

That’s exactly what Timeline reflects:

The results start getting better, frame-rate appears to have stabilized and, therefore, the animation runs smoother.

Running Animations in GPU

Let’s take it up a notch, then. To really get it running smooth, we’re going to use the GPU to render the animation.

.app-menu {

-webkit-transform: translateX(-100%);

transform: translateX(-100%);

transition: transform 300ms linear;

will-change: transform;

}

Though some browsers still need translateZ() or translate3d() as fallbacks, the will-change property is the future. This property promotes the elements to another layer, so the browser doesn’t have to consider the layout render or painting.

See how smooth that is? Timeline substantiates that:

The animation’s frame-rate is more constant and the animation renders quicker. But there’s still a long frame running there at the beginning: a little bit of a bottleneck at the beginning.

Remember the HTML structure we created at the beginning? Let’s take a look at how we controlled the app-menu div in JavaScript:

function toggleClassMenu() {

var layout = document.querySelector(".layout");

if(!layout.classList.contains("app-menu-open")) {

layout.classList.add("app-menu-open");

} else {

layout.classList.remove("app-menu-open");

}

}

var oppMenu = document.querySelector(".menu-icon");

oppMenu.addEventListener("click", toggleClassMenu, false);

Aha! We caused a problem here by adding the class to the layout div. This forced the browser to regenerate our style tree — and that affected the rendering performance.

The 60 FPS Smooth as Butter Solution

What if we create the menu outside of the viewport area? Having the menu in an isolated area will ensure that we only affect the element that we wish to animate.

So, we propose the following HTML structure:

<div class="menu">

<div class="app-menu"></div>

</div>

<div class="layout">

<div class="header">

<div class="menu-icon"></div>

</div>

</div>

And now we must control the state of the menu in a slightly different way. We’re going to manipulate animations in a class that we remove when the animation ends, by using the transitionend function in JavaScript.

function toggleClassMenu() {

myMenu.classList.add("menu--animatable");

if(!myMenu.classList.contains("menu--visible")) {

myMenu.classList.add("menu--visible");

} else {

myMenu.classList.remove("menu--visible");

}

}

function OnTransitionEnd() {

myMenu.classList.remove("menu--animatable");

}

var myMenu = document.querySelector(".menu");

var oppMenu = document.querySelector(".menu-icon");

myMenu.addEventListener("transitionend", OnTransitionEnd, false);

oppMenu.addEventListener("click", toggleClassMenu, false);

myMenu.addEventListener("click", toggleClassMenu, false);

Let’s put it all together and check the results. Here’s a complete fully-enabled CSS3 example, with everything in the right place:

.menu {

position: fixed;

left: 0;

top: 0;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

overflow: hidden;

pointer-events: none;

z-index: 150;

}

.menu--visible {

pointer-events: auto;

}

.app-menu {

background-color: #fff;

color: #fff;

position: relative;

max-width: 400px;

width: 90%;

height: 100%;

box-shadow: 0 2px 6px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.5);

-webkit-transform: translateX(-103%);

transform: translateX(-103%);

display: flex;

flex-direction: column;

will-change: transform;

z-index: 160;

pointer-events: auto;

}

.menu--visible .app-menu {

-webkit-transform: none;

transform: none;

}

.menu--animatable .app-menu {

transition: all 130ms ease-in;

}

.menu--visible.menu--animatable .app-menu {

transition: all 330ms ease-out;

}

.menu:after {

content: '';

display: block;

position: absolute;

left: 0;

top: 0;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

background: rgba(0,0,0,0.4);

opacity: 0;

will-change: opacity;

pointer-events: none;

transition: opacity 0.3s cubic-bezier(0,0,0.3,1);

}

.menu--visible.menu:after {

opacity: 1;

pointer-events: auto;

}

And what does Timeline show us?

Green bars for days, baby. Want to see a live example? Click here.